Their Own Stories: Voices from Middletown’s Melting Pot

For countless generations Mamoosan’s people, the Wangunks, had thrived here in a place they called Mattabeseck. But now, in the 1740s, Mamoosan (“Son of the Moose”) was among the handful of his people that remained. He surveyed what little was left of their vast ancestral lands and despaired. His people were destitute. Younger Wangunks, in search of a better life, had set off to join settlements of related Native Americans in northern New York. Reluctantly, Mamoosan, then 40, followed.

For countless generations Mamoosan’s people, the Wangunks, had thrived here in a place they called Mattabeseck. But now, in the 1740s, Mamoosan (“Son of the Moose”) was among the handful of his people that remained. He surveyed what little was left of their vast ancestral lands and despaired. His people were destitute. Younger Wangunks, in search of a better life, had set off to join settlements of related Native Americans in northern New York. Reluctantly, Mamoosan, then 40, followed.

Before the 1600s, the Algonquin-speaking Wangunks had dominated this area of Connecticut for centuries. They were a spiritual people who revered Manitou, the Great Spirit found in all living things and in the forces of nature. They made tools from stones and animal bones, cured animal hides for clothing, and carved canoes out of birch. Round-topped wigwams gave them shelter; game and fish fed them. They planted crops of corn, squash and sunflowers.

But the arrival of Europeans brought the beginning of the end of their way of life. Smallpox and other epidemics decimated Connecticut’s native peoples, who had no natural immunity to such diseases. When English families arrived in Connecticut, Sowheag, the Wangunks’ leader, sold large tracts of land to the colony, retaining two sections for his people: one on the east side of the Connecticut River, in what is now Portland, and another on the west side of the river stretching from today’s Newfield area to Indian Hill. On this promontory, Sowheag had built a fortification from which he could survey his domain.

At first the Wangunks and the English lived relatively peacefully side by side. But as the white colonists’ numbers increased, the Wangunks’ way of life began to fade. Englishmen’s farms crowded out game; ministers sought to “Christianize” the Wangunk children, and Puritan laws proscribed Native-American behavior, prohibiting the consumption of alcohol, or work and play on the colonists’ Sabbath.

In some parts of New England, hostilities erupted into brutal battles between the native people and the English settlers. In 1675 the bloody conflicts that characterized King Philip’s War destroyed many English settlements, but the impact on the native population was catastrophic. Large numbers were killed or driven away as refugees; others eventually retreated into small reservations.

In some parts of New England, hostilities erupted into brutal battles between the native people and the English settlers. In 1675 the bloody conflicts that characterized King Philip’s War destroyed many English settlements, but the impact on the native population was catastrophic. Large numbers were killed or driven away as refugees; others eventually retreated into small reservations.

Although Middletown was spared the bloodshed of King Philip’s War, the area felt its impact nonetheless. The settlers’ rule grew stronger, and the Wangunks’ numbers grew fewer as they sold off more pieces of their ancestral lands and moved away.

By the 1740s, when Mamoosan left his homeland to settle in New York State, only a remnant of his people remained. Many of them married into local African-American families; today some of their descendants still live in the community. Others died here, destitute and alone, their lands gone and heritage nearly forgotten.

Drawing of Mamoosan’s Tree

Frances E. Oliver, 1844. Pencil on paper

This huge sycamore tree served as shelter for Mamoosan

(“Son of the Moose”) during the mid-1700s.

As the Wangunks’ lands and opportunities here dwindled, many of them, including Mamoosan, moved to northern New York. They left behind the graves of their ancestors in a burying ground just west of what is now Newfield Street, nearly to Cromwell. Mamoosan journeyed back to Middletown every autumn, beginning about 1750, to visit his ancestors’ graves. The great sycamore stood nearby, and at night Mamoosan slept inside its hollow trunk.

As the Wangunks’ lands and opportunities here dwindled, many of them, including Mamoosan, moved to northern New York. They left behind the graves of their ancestors in a burying ground just west of what is now Newfield Street, nearly to Cromwell. Mamoosan journeyed back to Middletown every autumn, beginning about 1750, to visit his ancestors’ graves. The great sycamore stood nearby, and at night Mamoosan slept inside its hollow trunk.

In 1844, a Middletown woman named Frances Oliver sketched the tree–then 19 feet around–a few years before it came down.

Copies of Wangunk signatures

Original at Connecticut State Library

In 1673, Middletown’s English colonists officially re-purchased from the Wangunks the land already specified as Middletown, again designating two “reservations” for the Wangunks to inhabit. Both English and Wangunks signed the deed. As the Wangunks did not write English, they used different symbols–referring to their names, families, or clans–as their signatures on the 1673 land deed. Both males and females represented the Wangunks, while the English allowed only men to sign the document.

In 1673, Middletown’s English colonists officially re-purchased from the Wangunks the land already specified as Middletown, again designating two “reservations” for the Wangunks to inhabit. Both English and Wangunks signed the deed. As the Wangunks did not write English, they used different symbols–referring to their names, families, or clans–as their signatures on the 1673 land deed. Both males and females represented the Wangunks, while the English allowed only men to sign the document.

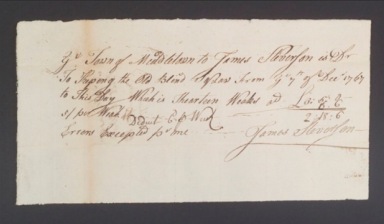

Bill to the town of Middletown

Before the welfare system existed, Middletown residents who were too poor or sick to care for themselves were forced to live with local people who then billed the town for their expenses.

In 1768, James Stevenson sent an invoice to Middletown’s selectmen, for compensation for “keeping the Old Blind Squaw…thirteen weeks…” The Wangunk woman in his care was Tyke, the elderly widow of Cushoy, who had signed the 1733 land deed with the English settlers. Tyke no longer had family members who could care for her, and had to rely on strangers.

In 1768, James Stevenson sent an invoice to Middletown’s selectmen, for compensation for “keeping the Old Blind Squaw…thirteen weeks…” The Wangunk woman in his care was Tyke, the elderly widow of Cushoy, who had signed the 1733 land deed with the English settlers. Tyke no longer had family members who could care for her, and had to rely on strangers.

Photograph of Ann Cornelius’s Gravestone

Old Burying Ground, Durham

A small number of Native Americans remained in the area during the late 1700s, many of them “Christianized” by the whites. Ann Cornelius was probably (judging from her name) among them, and at her death in 1776 received a Christian burial in Durham’s graveyard. But segregation existed even among the dead: most colonial cemeteries relegated non-whites to a separate section at the side or rear of the lot. The gravestone for Ann Cornelius, “Indian Girl,” stands at the very edge of the cemetery, far removed from those of the white residents.

A small number of Native Americans remained in the area during the late 1700s, many of them “Christianized” by the whites. Ann Cornelius was probably (judging from her name) among them, and at her death in 1776 received a Christian burial in Durham’s graveyard. But segregation existed even among the dead: most colonial cemeteries relegated non-whites to a separate section at the side or rear of the lot. The gravestone for Ann Cornelius, “Indian Girl,” stands at the very edge of the cemetery, far removed from those of the white residents.

Basket

Made by Esther Beaumont, probably mid-1800s

Courtesy of the Durham Historical Society

By the 1800s, only a few full-blooded Wangunks remained in the Middletown area. Some had married into local African-American families; others had left the area entirely.

Esther Beaumont, the Native-American woman who wove this basket, was born about 1797 and seems to have descended from the Wangunks through her mother, while her father was a Narragansett from Rhode Island. She married a Native American and after his death married Prince Beaumont, an African American and former slave. Esther lived in the Middletown/Durham area from the mid-1800s, selling her baskets to local people until her death in 1893. Her two daughters married local men who had African-American and Native-American blood.

Esther Beaumont, the Native-American woman who wove this basket, was born about 1797 and seems to have descended from the Wangunks through her mother, while her father was a Narragansett from Rhode Island. She married a Native American and after his death married Prince Beaumont, an African American and former slave. Esther lived in the Middletown/Durham area from the mid-1800s, selling her baskets to local people until her death in 1893. Her two daughters married local men who had African-American and Native-American blood.

Basket weaving was a craft handed down through the female line among Native Americans. Wangunk women probably had made baskets similar to this one for many generations.

Their Own Stories – Links

| Wangunks | English | Africans | |

| Irish | Germans | ||

| Poles | Jews | Greeks |